Further thoughts about the ex-Cook Collection Salvator Mundi*

The Leonardo Salvator Mundi controversy turns on which artist’s hand is – or which artists’ hands are – present on the painting. Many scholars agree that more than one hand is present. Here, it is demonstrated that while two hands are present, neither belongs to Leonardo. [M.D.]

Jacques Franck, an art historian and a painter trained in Old Master techniques, was a curator/exhibitor in the Uffizi Gallery’s exhibition “La Mente di Leonardo” (2006) and served on the International scientific committee advising the restoration of Leonardo’s St Anne in the Louvre (2010-2012), where he also advised the restoration of Leonardo’s Belle Ferronnière (2014-2015) and that of Leonardo’s St John- the- Baptist (2016). A regular contributor to scientific journals, he is completing a research thesis on Leonardo’s sfumato technique at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in Paris.

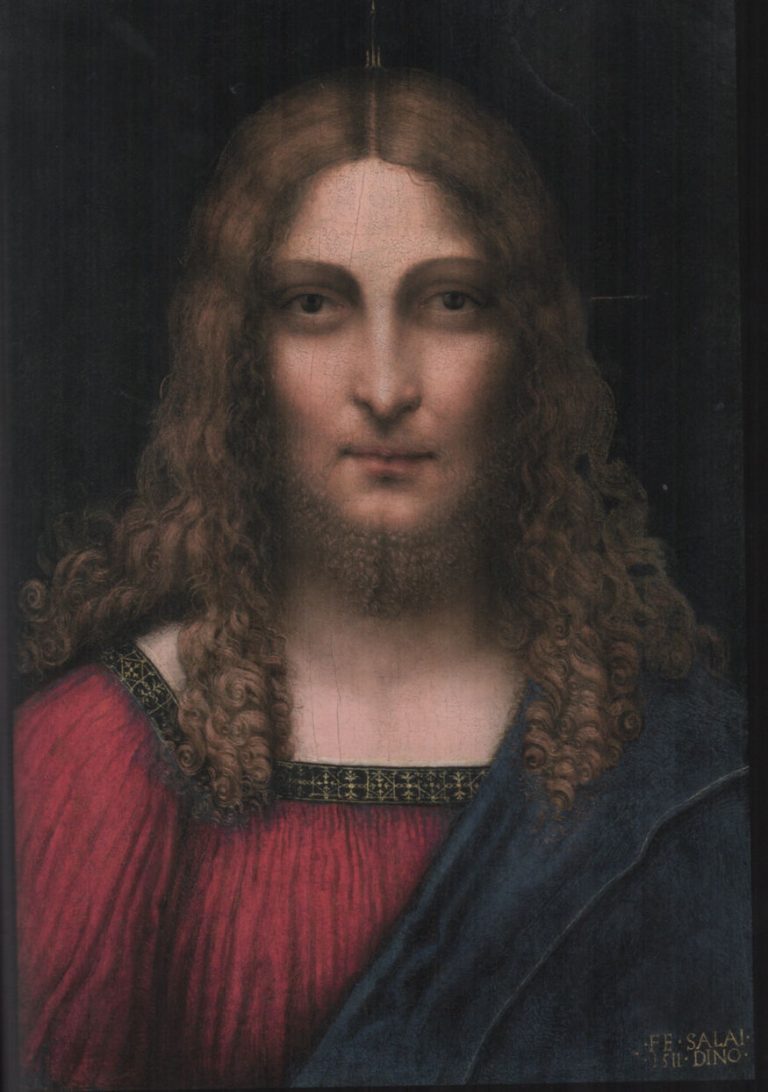

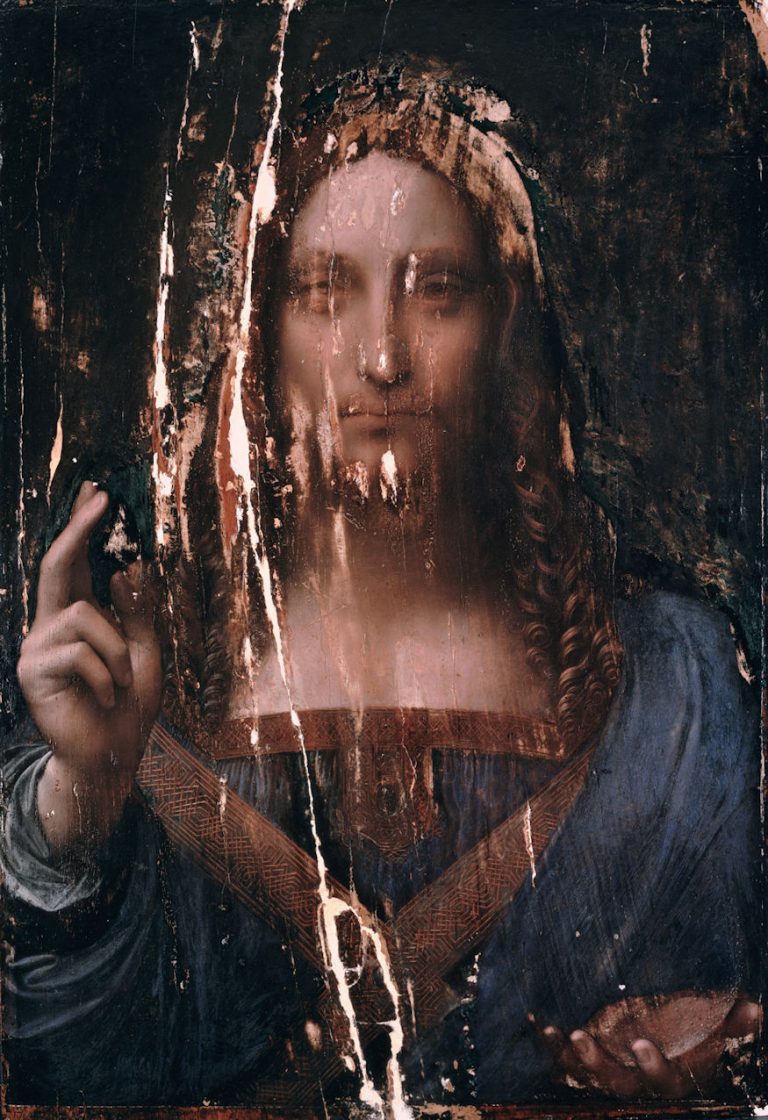

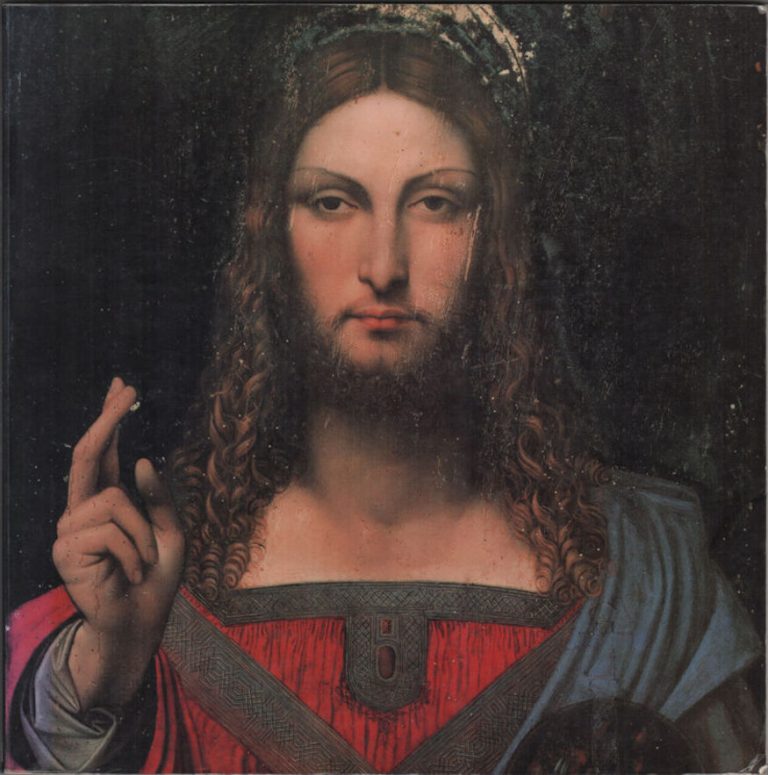

It is commonly believed in the art market that the more you argue and produce literature to defend a work’s authenticity, the less authentic it probably is. The Mona Lisa does not need any support to impose its genuineness as a heavenly Leonardo masterpiece and as such nobody has ever doubted it through the centuries, for it would appear nonsensical to any reasonable art historian. This is far from being the case with the Cook/New York version of the Leonardesque Salvator Mundi (Fig. 1, below) about which doubts have arisen all over the planet shortly after its first appearance as a newly-born Leonardo in London in 2011 at the National Gallery. Suspicion has reached such a point recently, that the work’s earliest supporters, Martin Kemp, Margaret Dalivalle and Robert Simon considered it necessary to publish in late 2019 a substantial three-part essay in defence of the painting – Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi & The Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts – that had originally been promised 2011. The following lines are by no means an attempt to discuss any of the latter authors’ positions, but are just an afterthought about what struck me most in the controversial panel when I first saw it several years ago. Given the existence of two drapery studies in Leonardo’s hand, kept at the Royal Library in Windsor Castle (Figs. 2 and 3, below) and close to the Leonardesque sequence of Salvator Mundi, no critic, among those less convinced of the master’s effective contribution to the actual making of the ex-Cook/New York Salvator Mundi has gone as far as doubting it completely. This must however be envisaged on serious material grounds and it would mean, as we shall see, a step forward in understanding studio practice in the master’s bottega. Besides the firm attribution to Leonardo himself by Kemp and others, three authors’ names have been suggested until now: those of Luini, by Matthew Landrus; Boltraffio, by Carmen Bambach; and Salai by Franck. Yet, except myself – on further thinking – none of the latter experts exclude, even as a minor share, the presence of Leonardo’s brushwork in various details of the composition. Consideration of these very different views, although seemingly paradoxical, might in part help solve the enigma concerning the organisation and mode of functioning of Leonardo’s studio.

Above, Fig. 1: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai with the assistance of G. A. Boltraffio or B. Luini?), Christ as Salvator Mundi, c. 1506/8-1513, oil on wood panel, 65. 5 x 45.1 cm (private collection).

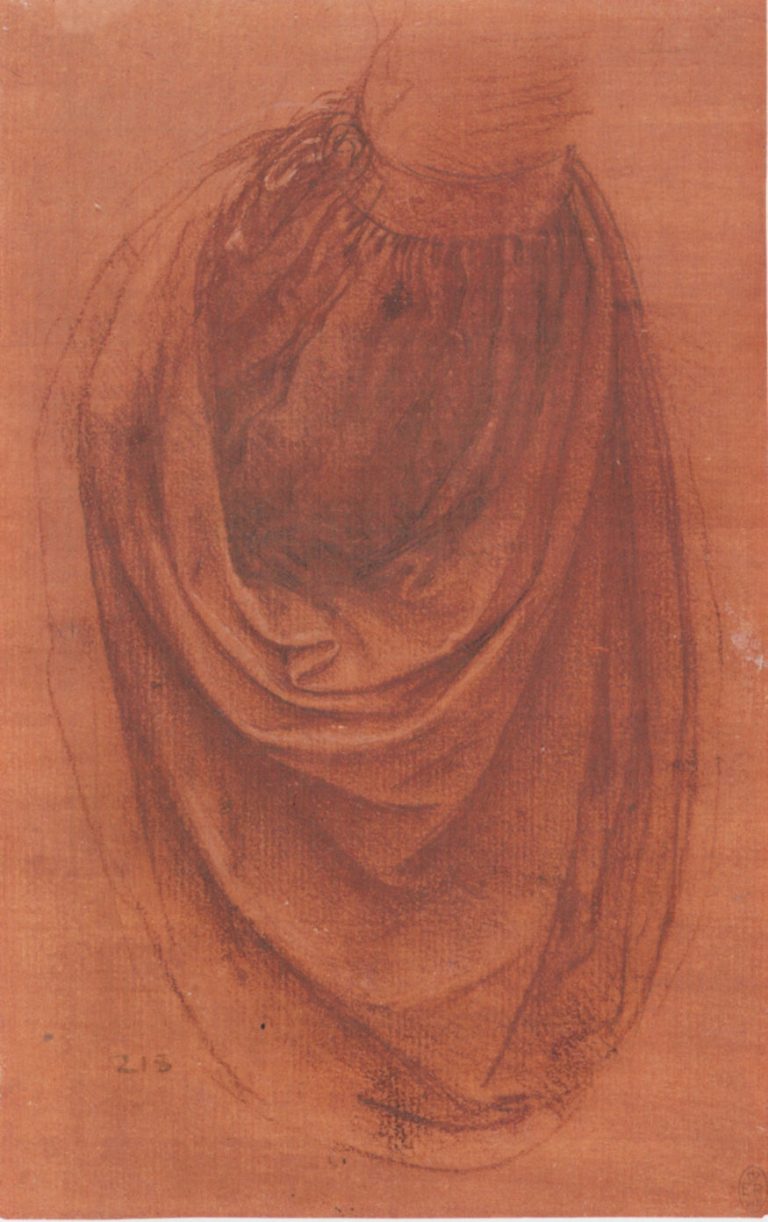

Above, Fig. 2: Leonardo da Vinci, Drapery study, c. 1506/8-1510, red chalk on prepared paper, 22 x 13.9 cm, Windsor Castle, Royal Library n° 12524.

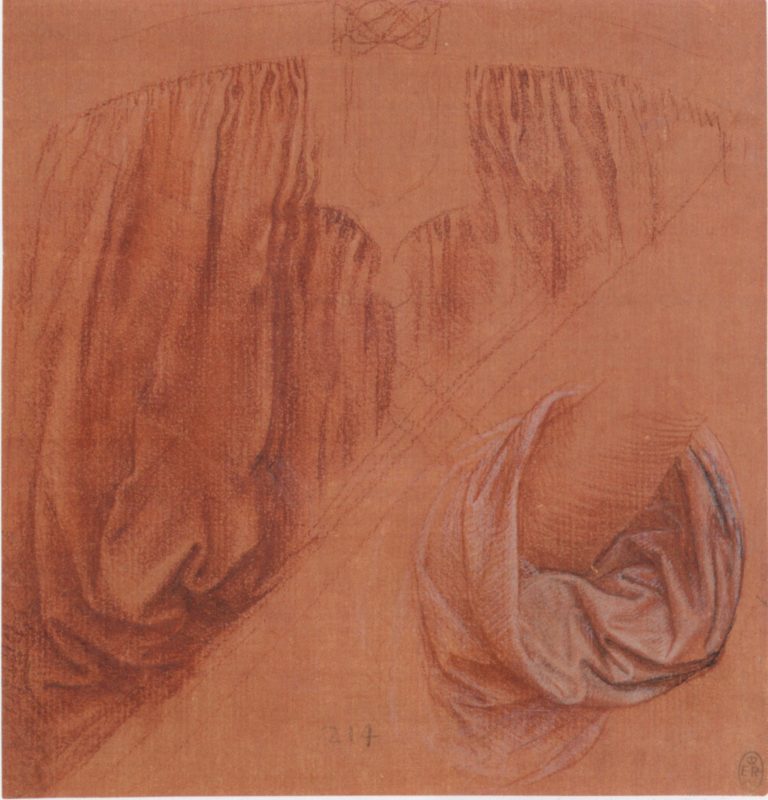

Fig. 3: Leonardo da Vinci, Drapery studies, c. 1506/8-1510, red chalk on paper, 16.4 x 15.8 cm, Windsor Castle, Royal Library n° 12525.

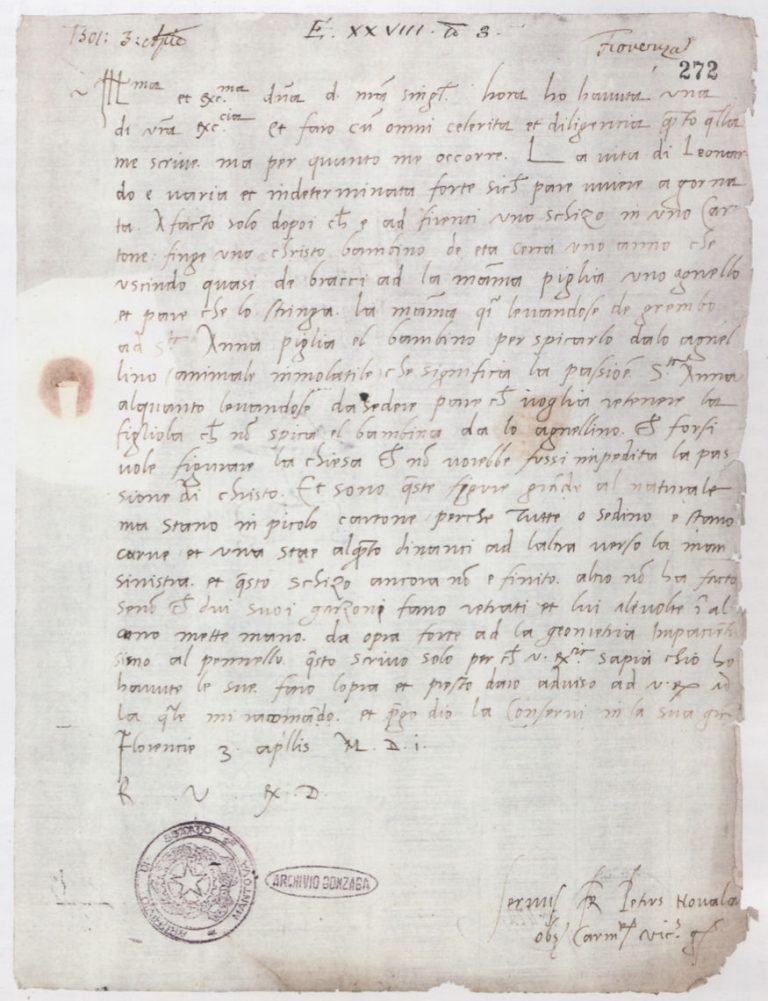

Above, Fig. 4: Pietro da Novellara, Letter of 3rd April 1501 to Isabella d’Este, marchioness of Mantua, Mantua, Archivio di Stato.

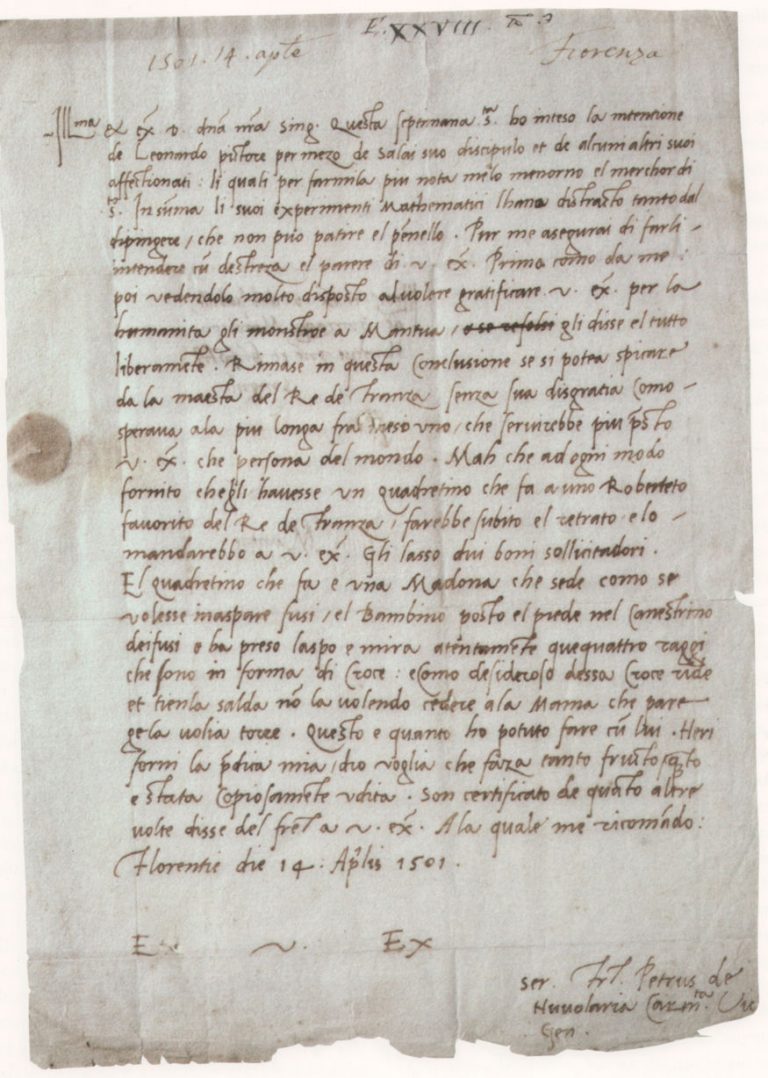

Above, Fig. 5: Pietro da Novellara, Letter of 14th April 1501 to Isabella d’Este, marchioness of Mantua, New York, private collection.

Above, Fig. 6: Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Isabella d’Este, 1500, black chalk, red chalk and ochre chalk on paper, 61.1 x 46.5 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

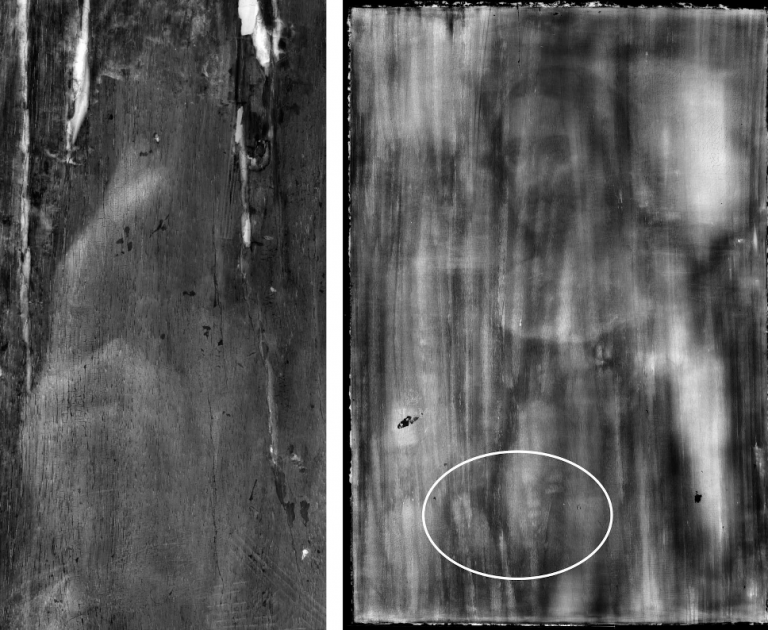

The situation can be summed up as follows: we know from two letters (Figs. 4 and 5, above) sent on 3 and 14 April 1501 by Pietro da Novellara, Isabella d’Este’s emissary in Florence, that Leonardo was overworked in those days, being involved in many projects while committed to the French King and his Court. Nevertheless, now and again the master – as is customary in art studios at all times – would retouch his assistant’s copies (or variants) after his works. Also, Salai, then twenty-one, appears to have become someone essential, holding a position of trust in the studio’s organisation (he was, for instance, instrumental in Novellara’s meeting with Leonardo). At this stage, he might well have taken over some commissions from Leonardo who, as we know, could not cope with the lesser ones not from the leading political powers – no painted portrait of Isabella or pictures meant for sacred purposes (i. e. any specific commission for an altarpiece) followed Leonardo’s drawn portrait of her (Fig. 6, above). Whatever the case, when comparing the infrared reflectograms of the New York Salvator Mundi and of Salai’s Head of Christ in the Ambrosiana (two works that bear numerous distinct material and aesthetic similarities that are strange to Leonardo’s own style and technique), evidence that Salai’s contribution to the New York panel was crucial cannot be discarded: the latter picture’s preliminary sketching out technique is without any doubt close to Salai’s own very recognizable practice, as observed in infrared light in his Head of Christ and other attributed works. The rarity of such a resemblance cannot be considered coincidental with paintings produced by one and the same studio (Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, below).

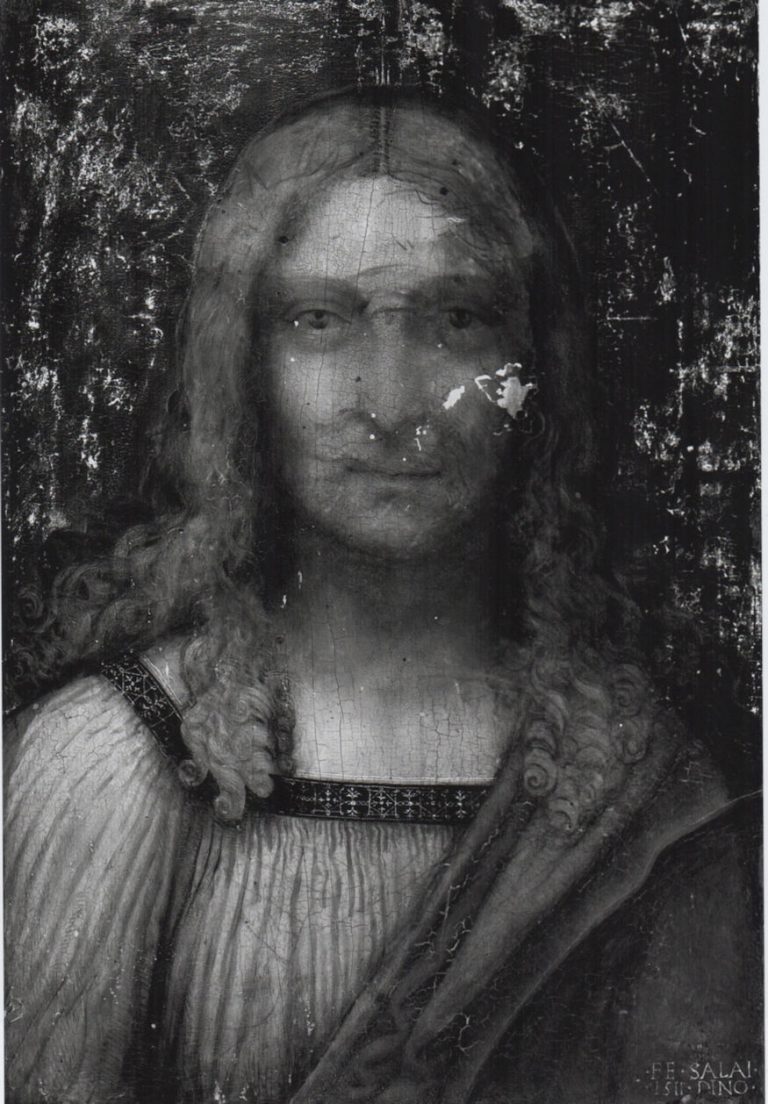

Above, Fig. 7: Salai, Head of Christ, 1511, oil on wood panel, 55 x 37. 5 cm, Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana. Salai’s Head of Christ (obviously deriving from a workshop Salvator Mundi prototype) testifies to what Christ’s face in the Cook/New York version of Salvator Mundi, now greatly damaged, including the eyes, probably looked like at the outset. The staring eyes with a ‘metaphysical’ expression were necessarily quite different when the now missing dark brown pigments forming the iris were still unimpaired.

Above, Fig. 8: Infrared scan of Salai’s Head of Christ. The infrared image of the panel reveals the underlying heavy, systematic and unmodelled dark contours outlining the shape of the head down to the shoulders and that of the face and neck.

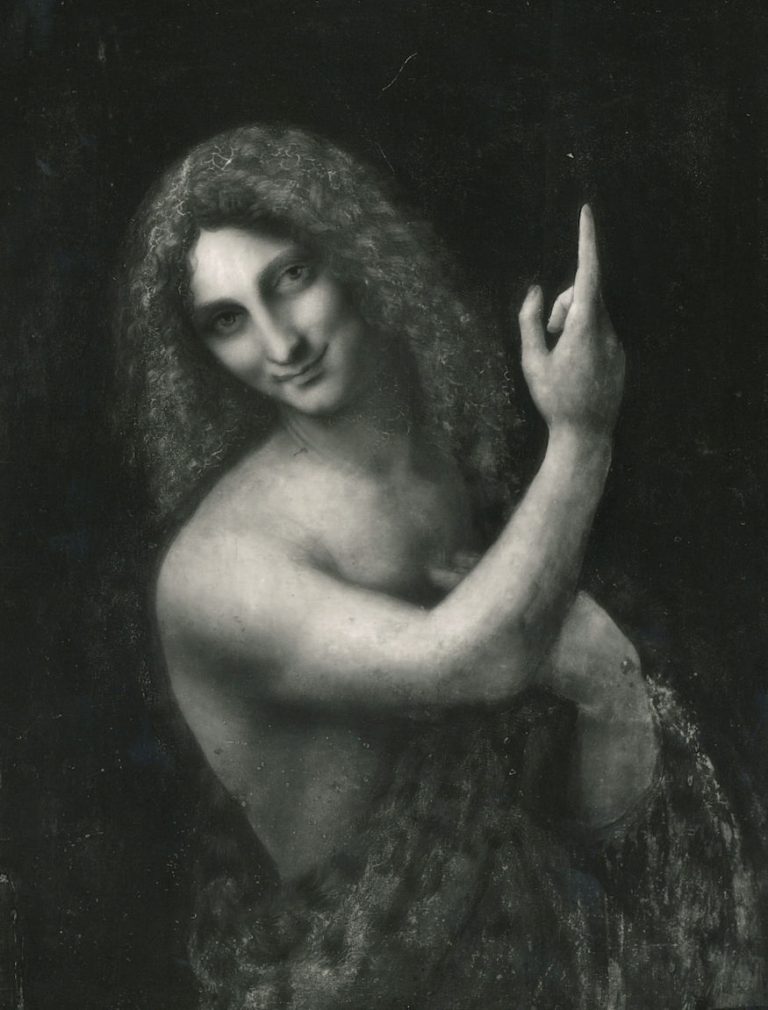

Above, Fig. 9: Infrared scan of the New York Salvator Mundi (a document of September 2007 that was not released on Dianne Modestini’s website, salvatormundirevisited.com, before 14 August 2020 (10 days after the present post’s release): the only IR scan reproduced there until then, still shown to date, was a later one made of the picture during the restoration process when the background was already repainted, hence the dark, blocked image in that section). Better preserved than the other zones of the composition, the oversimplified, thick and sharp outlining of the head (see upper right and top) compares well what is observed in Fig. 8, above: the sketching out work seems in the same hand. See also Fig. 11, below.

Above, Fig. 10: Infrared scan of the New York Salvator Mundi (detail of head).

Above, Fig. 11: Photograph in visible light of the New York Salvator Mundi before restoration (2006). Despite the heavy damage and paint losses, the thick outlining of the head, face and neck is still visible here on the right hand-side of the panel. Also, the intense sfumato effect in the face and neck now seen in the restored panel doesn’t show in the 2006 photograph. The recent conservation treatment seems to have introduced an inappropriate evanescence resembling Leonardo’s style of his late years. As revealed by the 2006 photograph, this section’s modelling was in fact firmer and the shapes better defined, thus much more consistent with the Ganay version (Fig. 24, below).

Above, Fig. 12: Infrared reflectogram of Leonardo’s Saint Anne in the Louvre (detail). No heavy outlining appears in the underdrawing of the head of Leonardo’s Saint Anne in the Louvre. The contours and undermodelling are light and subtle.

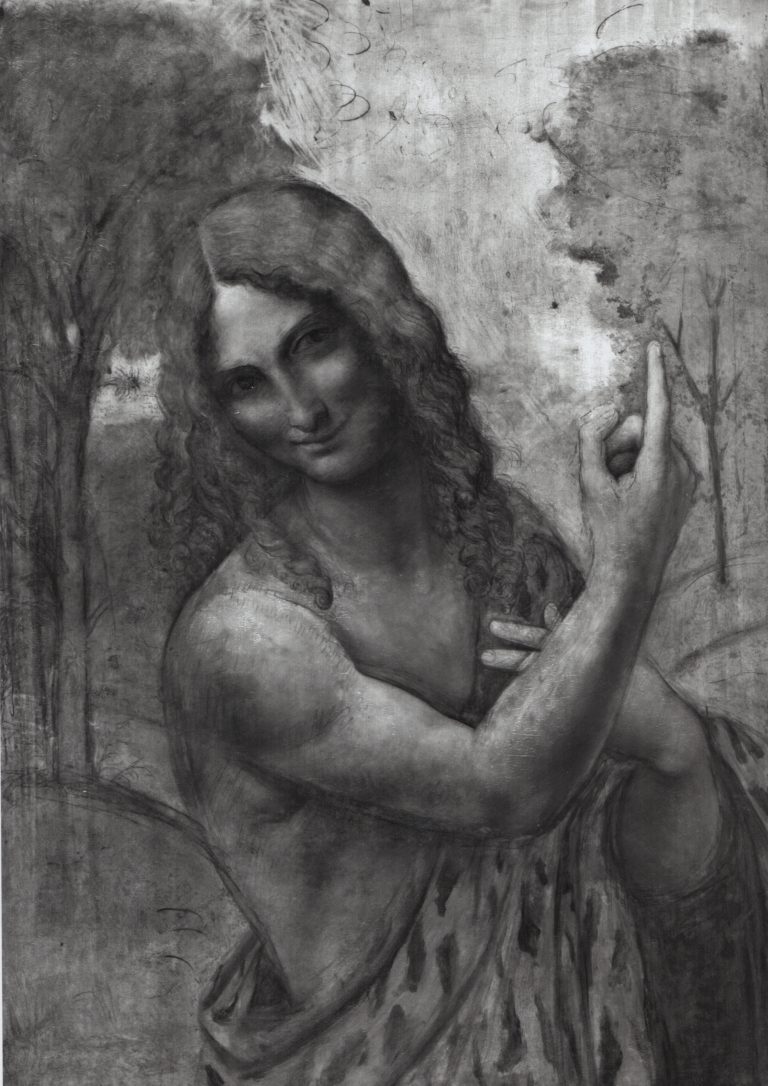

Above, Fig. 13: Infrared reflectogram of Leonardo’s Saint John-the-Baptist in the Louvre. Strong dark shadowing defines here the shape of the face and that of the neck. Yet, its treatment is not systematic, just softly blended and evanescent, contrary to the sharpness seen in most parts of Figs. 8, 9, 10 and 11, above.

Above, Fig. 14: Attributed to Salai, Saint John-the-Baptist in a landscape, c. 1508-1515 (?), oil on wood panel, 73 x 50. 9 cm, Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana.

Above, Fig. 15: Infrared reflectogram of Salai’s Saint John-the-Baptist in a landscape in the Ambrosiana. Another work after Leonardo traditionally attributed to Salai. Compare Figs. 8, 9 and 10, above: Salai’s heavy and very dark sketching out does not match Leonardo’s grace and subtlety perceivable even in the preliminary graphic stages of his own works (Figs. 12 and 13, above). No thick dark contour outlines the top of the Saint’s head because the background is a very luminous one here.

However, taking into account Novellara’s testimony regarding Leonardo’s occasional retouchings of his assistant’s copies, and, at the same time the existence of original red chalk drapery studies in close relation with the Salvator Mundi workshop sequence it has been assumed, yet without further development, that Leonardo acted in the making of the best parts of the 2017 New York sale picture – specifically, in Christ’s face and blessing hand. Within a standard scholarly rationale, such a scenario might well be considered acceptable, but it cannot be so considered from an experimentally and artistically informed perspective. Effectively, when addressing the pragmatic aspects of painting that are necessarily implied when assessing which part of a given work is attributable to one hand or another, historical research cannot sensibly proceed without investigating, as much as possible, the practical context of Renaissance art studios, in which sphere scholars often underestimate the highly informative potentials of artistic technical issues. In this regard, enough technical evidence of practice is displayed in the New York Salvator Mundi visually to help us grasp some basic information. Firstly, taking Leonardo’s original productions (both paintings and drawings) as a means of comparison, nowhere can be seen in his oeuvre as many inconsistencies as displayed here. Among them, the oddly long and thin nose, the simplified mouth, the over shadowy neck (with hardly any correctly defined anatomical detail in this large dark section), the stiff blue drapery, the mechanical hair ringlets, the childishly conceived left hand, the flat orb, and, above all, despite their neat finish, the wrongly raised fingers in the blessing hand, a quite inconceivable depiction from a brilliant artist like Leonardo. Secondly, what matters most is not this amount of clumsily painted details, because, while clumsy, they are still globally right, and thus plausible with regard to real life.

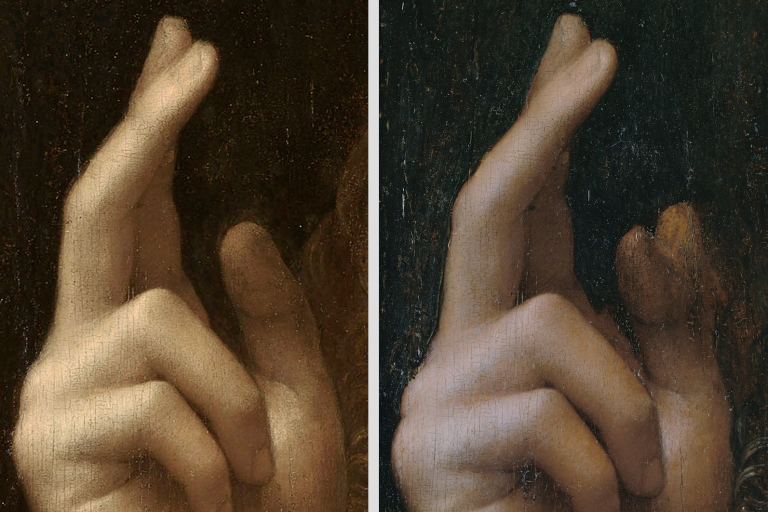

Much more preoccupying are the raised fingers, one of which rotates clockwise, displaying to the onlooker a full view of its nail, a detail that would be practically out of sight here should the rules of perspective be dealt with properly (Fig. 16a and 16b, below). Any academic art student well knows no teacher worthy of the name will accept anatomical inconsistency: it represents vis-à-vis classic art practice a fundamental transgression, much like false notes or rhythmical inaccuracy in classical music and must be deleted. Good art teachers always want that their students’ faulty anatomical forms be redrawn correctly. With Leonardo, a leading teacher and one of the greatest anatomists ever, there is little chance that he might have painted the faulty fingers, and hardly any possibility, either, that this anomalous detail be validated in one of his studio’s productions without a good reason. If anyone were to doubt this, it must be reminded that the Florentine artist had studied the movement of the hand and fingers extensively as appears notably in the Codex Atlanticus (fol. 124 verso (45 v-a) and fol. 273 a recto (99 v-a); J. P. Richter’s anthology, §§ 353-354). In addition, it should be noted that in various Christ Blessing painted by the Leonardesques in the same period (except for the studio Salvator Mundi copies in which the blessing hand is faithful to that in the Cook version – see Fig. 17, below -, following the master’s exemplary lesson (Fig. 16b, below), the finger movement of the blessing hand is perfectly correct (Figs. 18 and 19, below). Therefore, it is far from proven that the master, contrary to his own well-established concepts and practice, could have suddenly changed his mind about the orthodox representation of a human hand in a single picture and nowhere else in his other paintings.

Above, Fig. 16: [a] The New York Salvator Mundi (detail of blessing hand); [b] Leonardo da Vinci, the Annunciation, Florence, Uffizi Gallery, detail of the Virgin’s proper left hand (mirrored image showing the young Leonardo’s perfect treatment of a hand gesture close to the New York Salvator Mundi’s blessing hand).

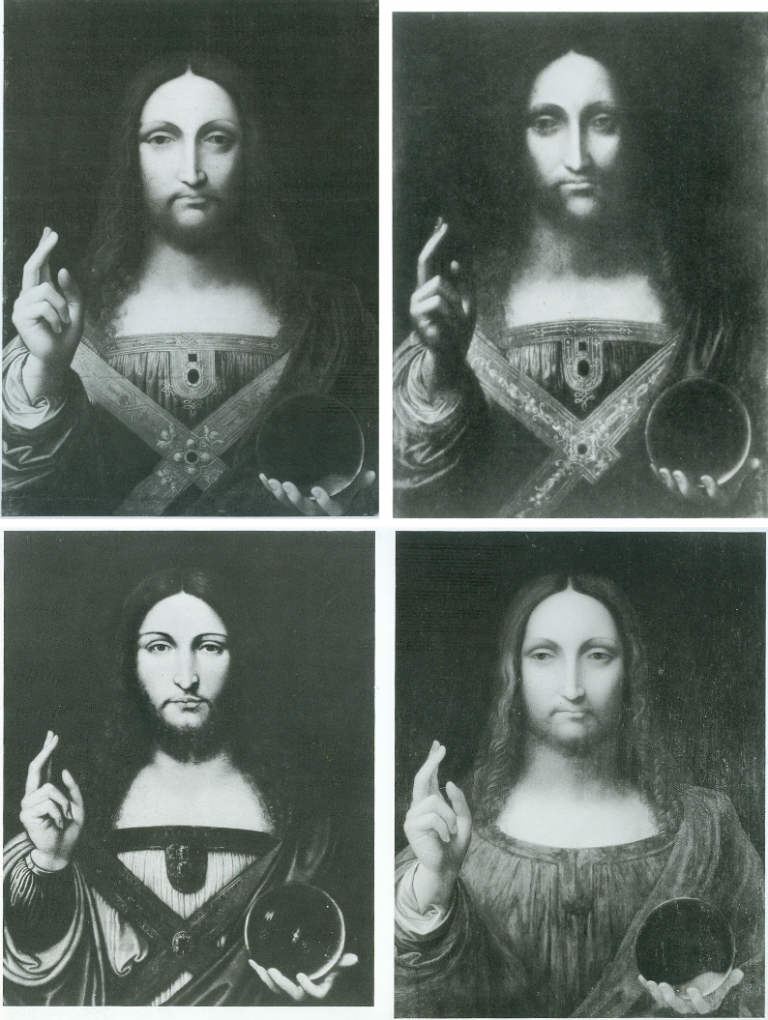

Above, Fig. 17: A sequence of 16th century variations after a Salvator Mundi prototype produced by Leonardo da Vinci’s main assistants c. 1506/8-1513. Compare the blessing hand in Figs. 1 and 16a, above.

Above, Fig. 18: Marco d’Oggiono, Young Christ Blessing, early 16th century, oil on wood panel, 35 x 26 cm, Rome, Borghese Gallery.

But if Leonardo had little to do with the New York Salvator Mundi beyond the Windsor sheets, who else might have improved the blessing hand to the point where its disputable anatomy and movement went unnoticed by many respectable scholars? The response lies explicitly in the fact that long before leaving Milan for several years in late 1499, Leonardo was in charge of an important studio and had to run it so as to have enough availability to face his very many and demanding activities as a military engineer, architect, cartographer, hydrologist, etc., and, at the same time, to honour various other commitments (in particular regarding the huge Sforza cavallo), or to organise festive Court celebrations inherent to Duke Ludovico Sforza’s service. It is therefore clear that his studio was assisted by excellent painters like Boltraffio, Marco d’Oggiono, Ambrogio De’ Predis and possibly other skilled, yet unrecorded artists, well before his return to Florence in 1500 after Ludovico’s fall. It must also be considered that, because he had the human and artistic means to perform such a challenge, in other words a well-trained team, Leonardo in person not only accepted but actually encouraged his best assistants to imitate his art to such a degree that no unspecialized onlooker would detect a difference. This was necessarily the case when the Cook version of the Salvator Mundi was painted (c. 1506/8-1513?), especially between 1506-1508 when, in Milan again, Leonardo was legally obliged to complete the Virgin of the Rocks, probably by then the London version (Fig. 20, below). In effect, rather than discern distinctly, one can guess in the altarpiece the presence of Boltraffio’s brush among other ones: the homogenous result of these intermingled contributions produces visually a global ‘Leonardo effect’ most difficult to dissect into recognizable individual styles. This aspect is particularly well illustrated with the Madonna Litta, to which Leonardo and Boltraffio had so tightly collaborated many years before, around 1490, that it is almost impossible to know who did what and where in the panel (Fig. 21, below). Later on, c. 1507/8-1513, another assistant and fully trained maestro, Bernardino Luini, whose presence in Leonardo’s bottega is not formally documented, just probable, would demonstrate his great ability to assimilate Leonardo’s style and technique. Many of his works betray this outstanding mimetic facility, in particular the handsome Christ Inv. 80 kept in the Ambrosiana in Milan (Fig. 22, below), whose blessing hand is strangely close to that seen in the Cook version of the Salvator Mundi, although Luini’s Christ’s correctly drawn limb doesn’t display the perspective and anatomical inconsistencies observable in the New York sale picture.

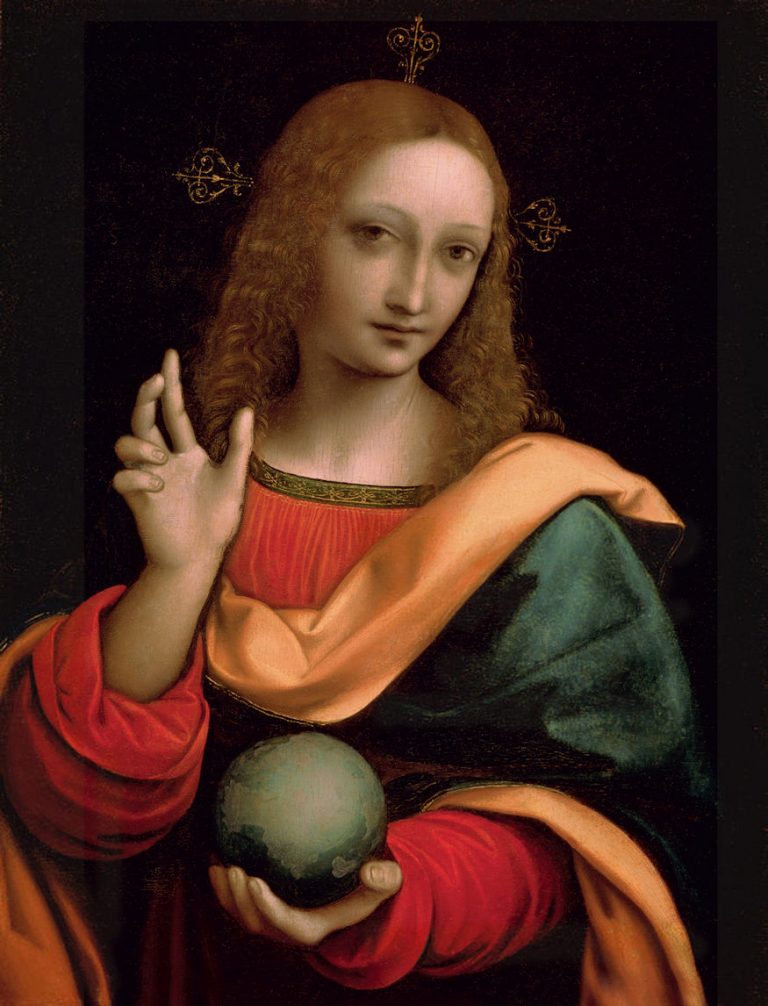

Above, Fig. 19: Giampietrino, Salvator Mundi, c. 1530 (?), tempera on wood panel, 50 x 39 cm, Moscow, Pushkin Museum.

Above, Fig. 20: Leonardo da Vinci and workshop, the Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1493/95-1508, oil on wood panel, 189.5 x 120 cm, London, National Gallery.

Above, Fig. 21: Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio under Leonardo’s supervision, the Madonna Litta, c. 1491-1495, tempera on wood panel transferred to canvas, 42 x 33 cm, St Petersburg, The State Hermitage. This small devotional painting has long been thought a genuine Leonardo until two preparatory studies in Boltraffio’s hand, completing Leonardo’s own project but paid little attention before 1990, were properly linked to the panel by D. A. Brown and M. T. Fiorio, thus proving that Boltraffio’s contribution was extensive. The particularly meticulous execution of the smooth and waxy sfumato in the flesh zones is very close here to the modelling encountered in the Salvator Mundi’s blessing hand (Cook/New York version, Fig. 16a, above).

Above, Fig. 22: Bernardino Luini, Christ Blessing, c. 1525 (?), tempera and oil on wood panel, 43 x 37cm, Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana.

Salai had of course never reached that level of accomplishment although by 1500-1510 he was probably in charge of the lesser commissions which Leonardo could not execute for want of time (some of the copies after the Louvre Saint Anne might testify to his specific involvement in the studio’s activity (Fig. 23, below). In my eyes it is doubtless that right at the outset Salai’s share in the New York Salvator Mundi prevailed and that Leonardo had practically none, because nothing that is absolutely typical of his own manner of making appears in the work. For example, on close examination it is obvious that the swirling folds in the sleeve of Christ’s blessing hand, a detail in which some specialists recognize Leonardo’s own hand, is in fact a very simplified motif taken from the far more complex Windsor drapery studies: any skilled collaborator could execute this passage with brio (Figs. 1, 2 and 3, above). However, given that the typology of the underlying layers in the New York panel so greatly resembles that encountered in Salai’s Head of Christ of 1511 in the Ambrosiana and – as noticed by me while completing this essay – in the Ganay version also (one, moreover, in which the design of the Saviour’s face strangely resembles Salai’s own Christ (Figs. 7, above, and 24, below), the debate can only waver over who handled the improvements and ‘finishings’ in the painting in attempt to make it as close to Leonardo as was the case with the Madonna Litta (albeit with Boltraffio’s involvement being far more important in the latter picture). Also, according to when the Cook version of the Salvator Mundi might be considered to have been painted, the name of Salai’s collaborator will emerge more conspicuously: Boltraffio is a likely candidate by, say, 1508, at the time he was perhaps helping Leonardo terminate the London Virgin of the Rocks, and Luini before Leonardo’s voyage to Rome in 1513. I would personally favour Boltraffio’s contribution because his assimilation of Leonardo’s style was perhaps even deeper than that of Luini – besides, he had known Salai for a long time and, for that reason, might have accepted to improve the blessing hand as a friendly move towards Leonardo’s protégé, hence the pentimento in the thumb. Boltraffio, for sure, was a great artist and no anatomical mistakes like that in the Salvator Mundi’s blessing hand are seen in his paintings. While the making process of the New York Salvator Mundi’s blessing hand and those in the Mona Lisa (Figs. 25 and 26, below) look roughly similar, the likeness is superficial and deceptive for a clear distinction exists both in terms of their technical executions and their visual effects. While the technique used in the Mona Lisa is much more evanescent and allusive to the tiniest detail, thus producing an impressive feeling of both real life and mystery, the careful, waxy modelling of the Salvator Mundi‘s blessing hand appears schoolish by comparison, with a touch of prettiness that is uncharacteristic of Leonardo’s usual vigour. Worthy of note, in the same zone, is the marked use of lead white as seen in the London Virgin of the Rocks, in which Boltraffio’s contribution can hardly be doubted (Fig. 27, below). The X-radiographs of both the New York Salvator Mundi and the Mona Lisa are most revealing about the different ways each artist followed to create the hands (Fig. 28 a and b, below).

Above, Fig. 23: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai?), the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and a lamb, c. 1508-1515 ?, oil on wood panel, 104.8 x 75.5 cm, Florence, Uffizi Gallery.

Above, Fig. 24: The Ganay Salvator Mundi (Leonardo’s workshop), unrestored, viewed in daylight (detail of head). Compare the thickish dark uneven curved outlining of the head (not to confuse with the perfect arc traced just above) as seen in infrared light in the New York Salvator Mundi (Figs. 9 and 10, above) and in Salai’s Head of Christ in infrared light also (Fig. 8, above). The similarity of the facial features in Salai’s Head of Christ and in the Ganay Salvator Mundi (especially the noses with a same shape and curvature) is striking. The obvious artistic/technical interrelation of both pictures with the Cook version of the Salvator Mundi tends to prove that Salai, beyond his own Christ, had a crucial part in the two other works probably jointly with a different artist each time. A very likely scenario since, in addition, the X-radiographs of both Salai’s Head of Christ and that of the Ganay version display global similarities, thus increasing the presumption of the three paintings’ mutual relation.

Above, Fig. 25: The New York Salvator Mundi (detail of blessing hand as in Fig. 16a, above). The sfumato effect here is very analogous to that in the Madonna Litta (Fig. 21, above), in the London version of the Virgin of the Rocks (Figs. 27a and b, below), in which Boltraffio’s noteworthy contribution is presumed, and also, to some extent, in Luini’s Christ blessing (Fig. 22, above). The sweet chalky flesh tones are due to the substantial use of lead white, a pigment producing a white image in X-radiographs.

Above, Fig. 26: Leonardo da Vinci, the Mona Lisa, c. 1501- 1510/15, oil on poplar, 77 x 53 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre (detail of hands).

Above, Fig. 27: Leonardo da Vinci and workshop, the Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1493/95-1508; detail of St John: [a] = In direct light, [b] = X-radiograph). [b] shows a white image in the sections containing a substantial quantity of lead white.

Above, Fig. 28: [a] = X-radiograph of the New York Salvator Mundi (detail of blessing hand), [b] = X-radiograph of the Mona Lisa (detail of hands section located by a white oval outlining). It is now an established fact that Leonardo uses less and less lead white in the flesh paint of his fully autograph paintings as his technique develops in subtlety, in particular from 1500 onwards. The X-ray characteristic densely white image revealing the use of lead white in paintings does not appear in the hands of the Mona Lisa, whose forms are not discernible here; conversely, the technique used in the blessing hand of the New York Salvator Mundi is proven very different by X-ray imaging, where the limb’s shape is distinguished clearly. While the latter work is contemporary with the Louvre masterpiece, its execution compares well that of the London version of the Virgin of the Rocks, from the same period also, a studio altarpiece in which Boltraffio’s contribution was very probable and the substantial use of lead white evident (Figs. 20, 27a and 27b, above).

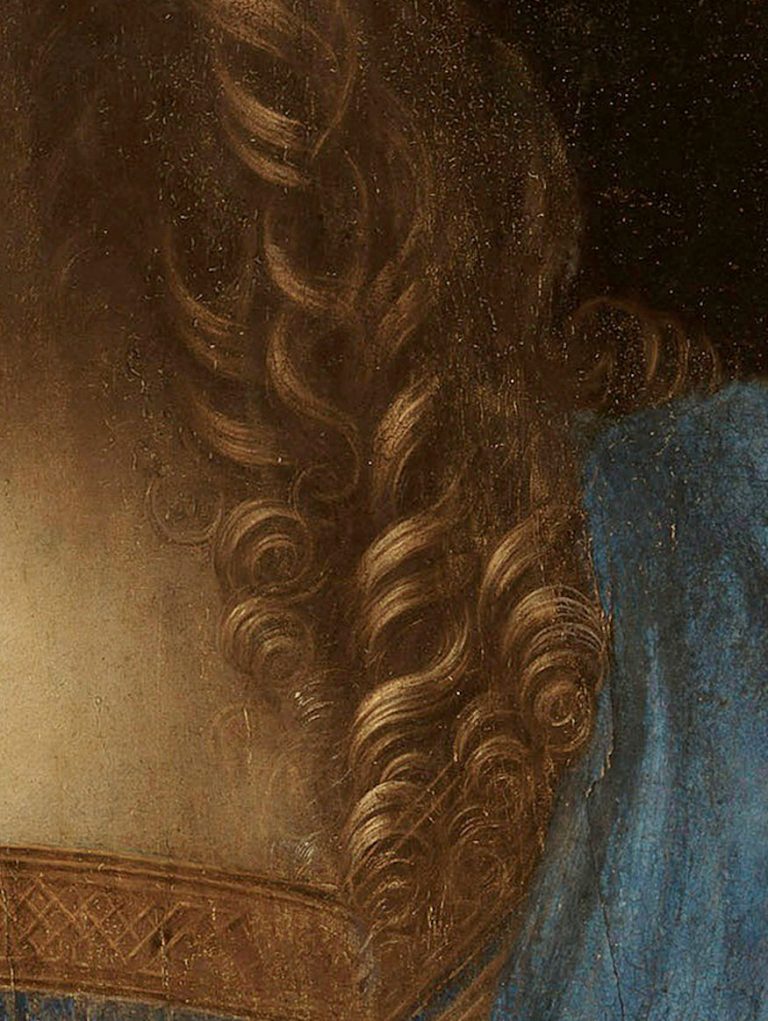

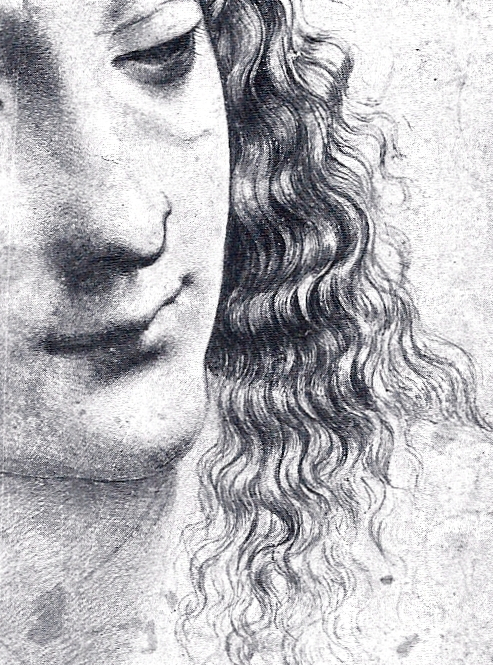

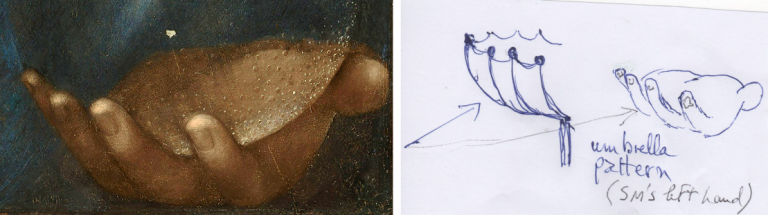

Incidentally, it has sometimes been hypothesized that Leonardo painted Christ’s face on the Salvator Mundi in an “out-of-focus” fashion, thus misty and blurred, in order to mark the spatial distance separating the face and the blessing hand and, thanks to this stylistic trick, suggest visually that the more distinctly shaped limb comes forward like in a real life 3-D effect. Yet, despite the ruined state of the picture when observed without any repaint, either old or recent, no such presumed artistic device can be seen in the otherwise unlike-Leonardo, heavy modelling of what subsists of the face: the overall treatment and definition of the values of light, shade and tone is exactly the same in both Christ’s face and blessing hand (Figs. 1 and 11, above). Whatever the case, a very interesting document appears to support the final supervision of the Cook version of the Salvator Mundi by Boltraffio: the impressive Study for the heads of the Madonna and Child in metal point kept in Chatsworth (Fig. 29, below) shows the extent to which Giovanni Antonio mimics Leonardo’s style (with slight departures that make a big difference) while displaying an unspontaneous, yet brilliant treatment of the Virgin’s hair in a graphic ‘hard-edge’ spirit close to Christ’s somehow systematic curls falling on His proper left shoulder (Figs. 30 and 31, below). A feature that is strikingly at variance with Leonardo’s usual treatment of curled hairs in his late years – as clearly appears in the Angel’s more evanescent and fluffy curls in the London version of the Virgin of the Rocks (the latter figure’s autograph status has always been accepted contrary to the rest of the Holy group) (Fig. 32, below). In fact, cork-screwing curled hairlocks are frequently seen in compositions not by Leonardo like, for instance, the Prado Mona Lisa, and the two studio productions of the Madonna of the Yarnwinder, one belonging to the Duke of Buccleuch, another kept in a private collection in New York (Figs. 33, 34a and b, 35a and b, below). More might be said on the inconsistencies in the New York Salvator Mundi panel, notably Christ’s proper left hand holding the crystal orb where the fingers are arranged in a strictly regular and unnatural sequence that somehow evokes the ribs of a small upturned umbrella (Fig. 36 a and b, below). Needless to say, such a solecism cannot denote Leonardo’s presence in that section – whereas, an additional pointer finally reveals that, if not Boltraffio in Leonardo’s studio, some other talented artist could have coped with the blessing hand without problem so as to make it closer to the master’s spirit: the remarkable Study of a hand in the Ambrosiana, sometimes attributed to Ambrogio De’Predis or to Marco d’Oggiono, is more eloquent than any words in this connection (Fig. 37, below).

Before ending, another oddity of the blessing hand should be mentioned, given its prime importance. Thanks to their precision, some remarkable visual documents reveal that the pentimento in the thumb increases the suspicion that Leonardo had little to do, if anything at all, in the making of the New York Salvator Mundi (Figs. 38a and 38b, below) . Interestingly, the Modestini cleaning has let emerge the initial form of the thumb, which, in fact, was shapeless and ill-defined at the outset, with two thumbs instead of one. Apparently, both were executed during the same painting session and not successively as is often thought. It might be considered that, following Leonardo’s well-known theory of componimento inculto (shapeless rough), the artist had sketched out two thumbs with a view to ultimately select the one best suiting his intentions. But this scenario is hardly acceptable: none of the initially elaborated thumbs is right in terms of anatomy and perspective. Both fingers have in fact been executed on the warm underpaint that served to make the brighter flesh tones, over which layer some basic modelling was painted with darker hues, yet, in each case the thumb was wrong. The more elaborate one, finally shaped as is seen today thanks to Boltraffio’s retouching (or whoever else did it save Leonardo), was seemingly meant to show the thumb’s first phalanx bent and not raised – while nearly in profile, a difficult angle to depict accurately even by a skilled artist. This was not really consistent with the position of the hand – already rather awkward – and this is why the wiser and easer solution was to show the inside of the thumb in front view, now raised and not bent anymore (but still wrong because not defined clearly, thus departing from the orthodox anatomy and movement of any human hand). The abandoned thumb was far too detached from the metacarpal bone to express what characterizes a natural hand gesture (a rough black outline along the right hand-side of that thumb could be an attempt to correct its faulty axis). Should any doubt subsist about Salai’s main authorship in the ex-Cook Collection Salvator Mundi, a further pointer would seem to contradict it doggedly: the confrontation of the unrestored blessing hand ( Fig. 38b, below) with the reversed infrared image of the Ambrosiana’s St John-the-Baptist (attributed to Salai, Figs. 14 and 15 above) reveals the strange similarity of the thumbs in each painting, including the hesitant positioning of the finger, a singular feature seen in both equally (Figs. 39a and b, below ). Under such circumstances, it is difficult to imagine that Leonardo contributed in this project materially, except for advocating the sensible, yet unsatisfactory, solution retained ultimately.

Above, Fig. 29: Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Study for the heads of the Madonna and Child, c. 1498-1500, silverpoint on paper, 29.7 x 22 cm, Chatsworth, Duke of Devonshire and Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement.

Above, Fig. 30: The New York Salvator Mundi (detail of Christ’s ringlets).

Above, Fig. 31: Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Study for the heads of the Madonna and Child (detail of the Virgin’s hair).

Above, Fig. 32: Leonardo da Vinci and workshop, the Virgin of the Rocks (detail of Angel’s hair).

Above, Fig. 33: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Salai?), the Mona Lisa, c. 1501-1515, oil on wood panel, 76. 3 x 53 cm, Madrid, Prado Museum.

Above, Fig. 34: [a] = Detail of curls in Leonardo’s Mona Lisa in the Louvre, [b] = Detail of curls in the Prado Mona Lisa. [a] displays Leonardo’s extremely natural depiction of the sitter’s hair curls in the legendary portrait while [b] reveals the studio’s mechanical treatment of the same detail.

Above, Fig. 35: 35) [a] = Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci, the Madonna of the Yarnwinder, c. 1501 (?), oil on wood panel transferred to canvas, 50.2 x 36.4 cm, New York, Private Collection, [b] = Detail of Madonna’s hair.

Above, Fig. 36: [a] = The New York Salvator Mundi (detail of Christ’s proper left hand), [b] = Umbrella pattern comparing the New York Salvator Mundi’s proper left hand.

Above, Fig. 37: Workshop of Leonardo da Vinci (Ambrogio De’Predis or Marco d’Oggiono?), c. 1495 (?), Study of hand, metal point and white highlights on light blue paper, 13 x 12.9 cm, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

Above, Fig. 38: [a] The New York Salvator Mundi (detail of blessing hand, restored stage); [b] The New York Salvator Mundi (detail of blessing hand rid of old repaints – see Fig. 11, above). As appears in [b], the dual, hesitant construction of the thumb reveals that its author was not very familiar with human anatomy. Quite obviously, Leonardo’s rigorous precepts to the painter in this field did not apply in any making stage of what stands here as a ‘theoretical hand’ and not one faithful to nature.

Above, Fig. 39: [a] The New York Salvator Mundi (detail of blessing hand rid of old repaints, like in Fig. 38b, above); [b] detail pasted from the reversed infrared image of Salai’s attributed St John-the-Baptist in the Ambrosiana (Figs. 14 and 15, above). A worthwhile comparison insofar as it helps to better situate Salai as an artist and his particular role in Leonardo’s bottega.

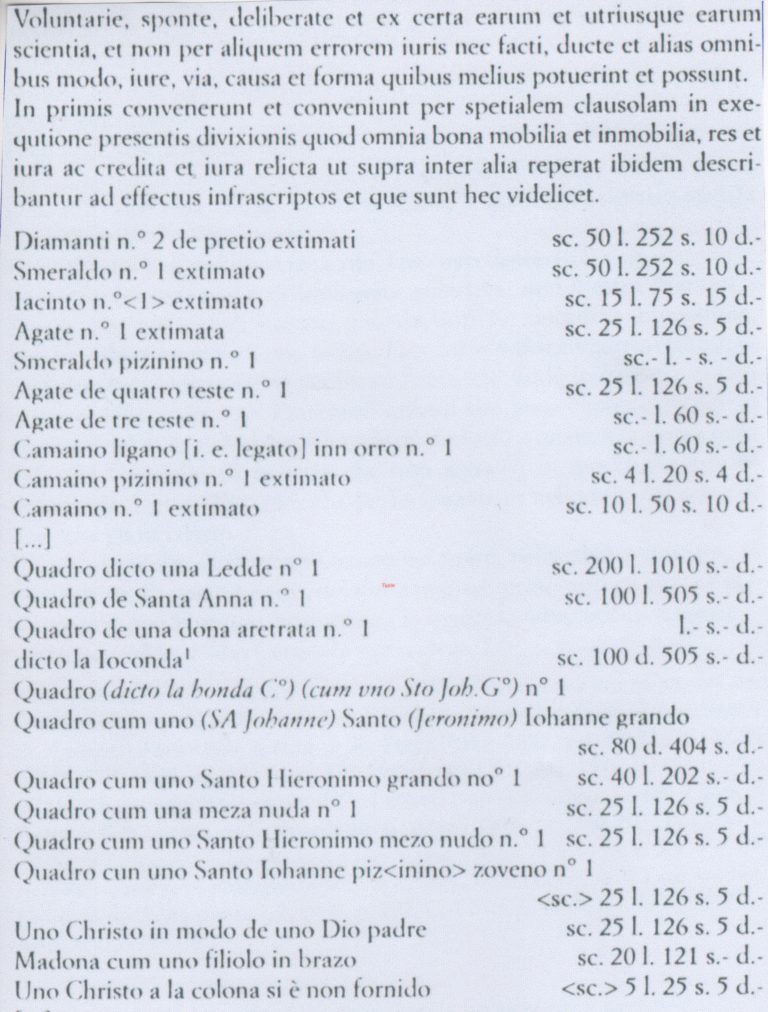

Above, Fig. 40: Extract from Salai’s posthumous inventory of the estate of 21st April 1525 (typed transcription).

Given the preceding, and contrary to the generally accepted idea, no determining fact or document proves that the studio productions deriving from Leonardo’s original compositions, whether painted or just sketched out graphically, were inevitably supervised and retouched in all cases by the master in person. And even if it were so, how much of Leonardo’s own work could be quantified in the New York panel as it stood before the recent conservation treatment? On visual examination of the relating technical image (Fig. 11, above), no essential detail suggests that Boltraffio would not have executed it jointly with Salai, especially as what has survived of the original paint layer, notably in Christ’s face and blessing hand, brings enough information to see that Leonardo’s faultless and easily recognizable brushwork must have vanished if the master ever contributed to the work’s execution significantly, because it is indistinguishable, thus missing entirely in the composition as it appears without the Modestini restoration, and so to the point that no claim of its hypothetical former existence can be sustained on sensible, scientific grounds. Against this absence of evidence of Leonardo’s hand on the Cook version of the Leonardesque Salvator Mundi, much solid material exists to propose another attribution that is entirely consistent with what the work really looks like – namely, Salai, jointly with Boltraffio. Such a conclusion, I believe, offers a better understanding of the studio works, which were produced by various permutations of collaboration, in which the master is close spiritually, yet not quite there. It should be noted, additionally, that beyond the above-mentioned artistic and technical flaws, doubts about Leonardo’s authorship are the more justified as a Salvator Mundi painting is recorded and priced 25 scudi in Salai’s posthumous inventory of the estate established on 21 April 1525: “Uno Christo in modo de uno Dio padre”, which was the then designation of such a visual representation of Christ (Fig. 40). Therefore, despite that concise – yet very clear – mention, no objective element opposes the identification of the ex-Cook Collection Salvator Mundi with the recorded Christo since, 1) the New York sale’s IR imaging displays technical features consistent with Salai’s sketching out practice, 2) no documented eventual provenance of this kind has been connected to Leonardo himself by far until now.** (A and B.)

Finally, because Leonardo stands among the greatest artists that ever existed, it is always tempting to increase his very restricted pictorial corpus with works that fall short doing it full justice. Yet, art at this level of accomplishment cannot be speculated about without the necessary critical approach and minimum knowledge of how Renaissance painters used to proceed in their creation, – mostly founded on perfect drawing – especially as in Leonardo’s case, his Treatise on Painting delivers crystal clear data to the researcher regarding its authors’ supremely elevated standards. We must therefore face the truth: this latest case of an upgraded studio item does no justice to Leonardo’s genius; it does not correspond to the highest standards encountered in his original autograph works and theoretical writings on painting. As such, its attribution to Leonardo himself must be rejected and given now, more appropriately, to his close circle of collaborators working on their own while still depending from the master’s occasional suggestions, whether drawn or verbal***.

* I wish to thank Michael Daley warmly for welcoming the present contribution of mine on the ArtWatch UK website and for having adjusted its presentation with the utmost care and kindness.

**A: On this point see in particular, G. Bora, D. A. Brown, M. Carminati, M. T. Fiorio, P. C. Marani, J. Shell, The Legacy of Leonardo. Painters in Lombardy 1490-1530, Skira Editore, Milan, 1998.

**B: See J. Shell and G. Sironi, “Salai and Leonardo’s Legacy”, in The Burlington Magazine,, CXXXIII, no. 1055, pp. 95-108.On Salai’s own pictorial production listed on the 1525 posthumous inventory and the original Leonardo paintings (including the Mona Lisa) which he sold to king Francis I in 1517-1518, see B. Jestaz, “François 1er, Salaï et les tableaux de Léonard”, Revue de l’Art, no. 126, 1999-4, p. 68-72.” On a specific agreement between Leonardo and Ambrogio de’ Predis about the master’s moral rights over the copy of the Virgin of the Rocks, see Grazioso Sironi, Nuovi documenti riguardanti la ‘Vergine delle rocce’ di Leonardo da Vinci, Giunti Barberà, Florence, 1981, p. 23-25 (document VII of 18 August 1508).

*** The recent cleaning of the Louvre’s Bacchus (initially painted as St John in the Wilderness) has revealed that this workshop composition of a higher artistic status than that of the Cook Salvator Mundi did not include the master’s material contribution although he had drawn an elaborate preparatory red chalk study for it (whereabouts unknown since 1973).

Jacques Franck, 3 (& 24) August 2020.

Leave a Reply